The Garden of the Phoenix

The Future Rises

In Chicago's Jackson Park, our future is growing from the past.

The new Garden of the Phoenix symbolizes Japan and the U.S.'s 160-year story of friendship, turmoil and prosperity. This park, home to SKYLANDING by Yoko Ono, a revitalized landscape, and future pavilion, is a public space to reflect on our history and watch the future rise.

Explore the park's stories on the map or in the full timeline.

Introduction

Our Stories Connect Us

From the opening of Japan in 1853 to the arrival of the Phoenix Pavilion for the 1893 Columbian Exposition to the new Garden of the Phoenix, this timeline explores the stories that connect Japan and the U.S. Though there have been chapters of highs and lows, we celebrate mutual understanding and years of friendship.

Scroll to watch the full story unfold or explore the chapters that connect with you. Each chapter has a gallery of images and articles to help you learn more.

Chapter 1

1853-54

Trade with Japan begins

Japan Opens Its Gates

After ratifying California as a state in 1850, the U.S. became a Pacific nation and quickly turned its attention to Asia.

The U.S. committed to ending Japan's nearly 250-year policy of almost total seclusion. In July 1853, a fleet of black gunships entered into what is now called Tokyo Bay. Its commander, U.S. Commodore Matthew C. Perry, delivered a letter from President Millard Fillmore to the Japanese government that demanded the opening of trade relations. He promised to return early the next year to receive a reply.

Chapter 2

1859-62

Yokohama Settlement

The Mercantile Settlement of Yokohama

The Treaty of Kanagawa, signed in 1854, allowed trade with the opening of Japanese ports.

A complete commercial treaty was negotiated by Townsend Harris, America's first consul to Japan, in 1858. This treaty, and those following, established foreign concessions, extraterritoriality for foreigners, and favorable import taxes for foreign goods. It also permitted the U.S. to open five ports, setting the stage for a foreign mercantile settlement on the small, man-made island of Yokohama.

A home to foreigners and locals

The modest settlement, only two miles-square and surrounded on all sides by water grew steadily

from its founding in 1859, likely due to its proximity to Edo (later known as Tokyo). Both locals and foreigners lived in Yokohama, but residences and businesses of the Japanese and the Westerners were divided by a main road, known as Honchō dōri (main street). There were four gates out of the area, and traffic was carefully monitored.

Curiosity about the westerners

The settlement in Yokohama, which had about 400 foreign residents by 1866, was the subject of intense interest

by the surrounding Japanese population. Print publishers did a brisk business of selling woodblock prints depicting the Americans' strange customs and appearance.

Revere the Emperor, expel the barbarians

Sonnō jōi, or “Revere the emperor, expel the barbarians” was a political slogan used during the 1850s and 1860s.

This phrase was used by local opposition to the Tokugawa government, which proved powerless to protect Japan against the foreigners. Following the restoration of imperial power in 1868, this slogan was replaced by fukoku kyōhei, or "rich country, strong military," which became the rallying call of the Meiji Period and the seed of Japan's actions through World War II.

Chapter 3

1860

Japanese Delegation Arrives

Japanese delegation established

Following the signing of the 1858 Harris Treaty, a delegation of Japanese ambassadors was formed to visit Washington, D.C. and ratify the treaty.

The Japanese set sail for America in February 1860, where they were to stay for nearly 10 months and visit the cities of New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore, in addition to the capital. The timing was awkward when the Japanese delegation, numbering 77, arrived in the U.S., as both nations were on the brink of civil war.

Chapter 4

1861–72

Destruction & Peril

Chicago goes up in flames

On the evening of October 8, 1871, fire erupted in Chicago, destroying thousands of buildings and leaving an estimated 300 people dead.

Legend has it the fire was started by a cow owned by Mrs. Catherine O'Leary that had knocked over a lantern, but the real cause is unknown. The Great Chicago Fire burned for three days, creating destruction over a widespread area that extended north to Fullerton Avenue and south to Harrison Street. The city was left with nearly $200 million in damages.

Chapter 5

1873–89

Revival & Progress

Chicago rises from the ashes

Starting the decade as a modest city of under 300,000, Chicago reinvented itself into a city with a population of more than a million

by the time of the World's Fair in 1893. As railroads reached to the Pacific Ocean, Chicago's strategic place on transportation routes assured its population and industrial growth would continue unabated for years to come.

Japan: An industrial and military force

Having emerged from shogunal rule, Japan's main city of Tokyo prospered

in the new quest for industrialization and military might. Bunmei kaika 文明開化 ("Civilization and Enlightenment") was a call to action that accounted for the adoption of Western ideals of architecture, commerce, and education.

Chapter 6

1890-93

1893

World's Fair

Chicago Chosen to Host World's Fair

On December 24, 1890, President Benjamin Harrison announced,

"In the name of the Government and of the people of the United States, I do hereby invite all the nations of the earth to take part in the commemoration of an event that is pre-eminent in human history, and of lasting interest to mankind."

The City of Chicago was selected to host one of the most important international events in the country's history—a world's fair to commemorate the 400th anniversary of Columbus' discovery of the New World in 1492.

Vision of Burnham and Olmsted

Two of country's leading designers were appointed to turn a nation's dream into reality.

Daniel Burnham was named Director of Works, responsible for the design of what would come to be known as the White City, with its glimmering Beaux-Arts buildings. Frederick Law Olmsted, the preeminent landscape designer responsible for New York's Central Park, was to create the outdoor elements.

The White City Is Born

Seemingly overnight, Chicago's Jackson Park, on the south shore of Lake Michigan, was transformed

from sand and marshland into an electrified city of gigantic neo-classic buildings for the World's Columbian Exposition. The Exposition opened in May and ran through October 30, 1893.

A spectacle for the world

Millions of visitors would come from around the world to see the best examples of industrial, scientific, and artistic talents of the day.

The main goals of the fair were to show a strong, unified America as the pinnacle of culture and showcase leadership in technology and commerce. The original Ferris wheel, the first moving walkway, life-sized replicas of the Nina, Pinta and Santa Maria ships, and showcases by 46 countries were among the sights on display for visitors.

Chapter 7

1892-93

Japan's Pavilion

Elevating Japan's stature

Japan's goal for the exposition was to establish itself as a modern, industrial nation that was open to trade and triumphant over unequal treaties.

To show the world how it had progressed in only 40 years, Japan prepared the most elaborate plans and largest budget—nearly $600,000—of any nation. In June 1890, leaders travelled to Chicago to negotiate the best locations for exhibits. After securing main exhibit halls to display the fruits of its rapid modernization, Japan sought a site for a building that could properly introduce the world to its rich artistic heritage, culture, and traditions.

The Phoenix takes flight

The Phoenix Pavilion was modeled after a noted building called the Hō-ō-dō, or Phoenix Hall, located in Uji, near Kyoto.

Built in 1052, the Phoenix Hall is recognized as one of the most important examples of classical Japanese architecture, and remains a symbol of Japan today. The Chicago version was given the name Hō-ō-den, or Phoenix Pavilion, signifying that it was modified from a sacred Buddhist temple building to one of secular purpose.

Opening ceremony

"As it is, it was an unexpected coincidence that the Phoenix Palace should have been in the City of Phoenixes."

On March 31, 1893, the finished Phoenix Pavilion was opened amid ceremonies attended by hundreds consisting of speeches made by the Japanese commissioners as well as the directors, commissioners, and chiefs of the fair on the U.S. side. It was no coincidence that that day marked the 40th anniversary of the signing of the first trade treaty between the U.S. and Japan.

Inside the Phoenix Pavilion

Representing a phoenix, the pavilion consisted of a central hall with two identical smaller structures situated on each side that were connected by roofed walkways.

The exteriors and interiors of these three structures were carefully imagined to showcase different historical eras of Japanese art—the Heian (Fujiwara) period of 794–1185, the Muromachi (Ashikaga) period of 1376-1573 and the Edo (Tokugawa) period of 1615–1868, the latter taking up four rooms in the central hall. This meant that, in one afternoon, you could imagine yourself inside of a courtier's residence, a shogun's castle, and a medieval tearoom.

The Art of the Phoenix

Students of the Tokyo School of Fine Arts, led by Okakura Kakuzō, carefully crafted paintings and artistic objects of the interior with historical accuracy.

Okakura's 1893 book An Illustrated Description of the Hō-ō-den (Phoenix Hall) at the World's Columbian Exposition was the official guide to the building's features, including its interior artwork and furnishings. The book's cover features stylized depictions of phoenixes among paulownia trees, a recurring motif in the building. It is reproduced here in its entirety.

Exhibits popular with visitors

Japan had spacious exhibitions throughout the fair in addition to the Phoenix Pavilion.

For example, the Japanese teahouse that was located on the Midway Plaisance became a very popular attraction that let visitors sample different kinds of green tea. And for the first time, Japan took part in the fine arts display at a world's fair, alongside America and European nations. Works shown here included artforms in which Japanese artists excelled such as ink painting, cloisonné, and textiles.

Chapter 8

1893–1923

Frank Lloyd Wright

Inspiration for a young architect

Architects from all over America were fascinated by the Phoenix Pavilion. Perhaps the most notable was Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959),

who was only twenty-six years old at the time. For Wright, who would go on to become one of the most important American architects of the twentieth century, this first encounter with Japanese architecture was a revelation.

Wright visits Japan

Wright's first trip outside the U.S. was to Japan in 1905, where he spent a few months touring the landscape and architecture from Nikkō to Takamatsu.

Shortly after his visit, he would begin discussions about designing the new Imperial Hotel. He traveled back to Japan in 1913 to examine its proposed location and sketch initial designs. His plans were approved April 1916 and he would return to Japan at the end of the year to prepare for the construction.

A hotel to bridge two countries

Wright had the opportunity to honor Japan when he was commissioned to design the new Imperial Hotel.

The completed building would become one of the most important ones in Tokyo by its completion in 1923. Inspired by the Phoenix Pavilion, Wright created a technical and aesthetic bridge between East and West, and hoped to inspire Japanese architects to create from their soul, rather than imitate the architectural styles of other countries. Being neither entirely Japanese nor completely Western, the hotel was a world in itself—intended as a unique place where people of different cultures could meet on equal terms.

Wright and Japanese art

Frank Lloyd Wright was a renowned collector and dealer of Japanese prints, often selling them as the perfect decorations for Wright-designed homes.

He noted in "The Japanese Print," a short book published in 1912, "These simple coloured engravings are indeed a language whose purpose is absolute beauty." Wright consistently lent prints to the Art Institute of Chicago, but his most important exhibition was undoubtedly a large 1908 installation where he displayed these prints in specially-designed frames. For the first time in Chicago, visitors witnessed a staggering array of prints from a variety of artists and time periods, most of which were owned by Wright himself.

Chapter 9

1894–1923

Jackson Park's Next Chapter

Urban oasis for city dwellers

Following the close of the 1893 Exposition, Jackson Park transformed from the White City into a pastoral urban setting

for people to connect with nature and each other. As the neo-classical buildings and canals were dismantled and faded into history, a rugged interconnected system of serene lagoons with lushly planted shores, islands, and peninsulas emerged throughout this remote 600-acre (2.4km2) parkland.

Chapter 10

1930s

1933

World's Fair

Marking "A Century of Progress"

Chicago's 1933 World's Fair was held on the 100th anniversary of its establishment

as a town, and, as its name suggests, featured the advances that Chicago and society in general had made in that time. Opened for 150 days, it focused on scientific discoveries and breakthroughs in communications and transportation.

Chapter 11

1934-36

Japanese Garden

Breathing new life into the Phoenix Pavilion

On July 27, 1935, the Chicago Park District opened the new Japanese garden, along with the restored Phoenix Pavilion.

This timing coincided with the arrival of Sadao Iguchi, the newly appointed Consul General of Japan at Chicago. Visitors could experience the Japanese teahouse, lanterns and torii gate that had been a part of Japan's exhibit at the 1933 World's Fair. During the final inspection before public opening, the Japanese Consul remarked, "Our people will always be grateful for what Chicago has done for this place. We revere this ground as a bit of our homeland transplanted in the heart of a great and friendly nation."

Chapter 12

1935–46

The Osato Family

The garden's caretakers

Shoji Osato and his wife, Frances Fitzpatrick, were entrusted by the Chicago Park District to care for the revived Phoenix Pavilion and garden.

The family would care for this site from 1935 through 1941. During this brief period, the Phoenix Pavilion and its garden became, arguably, the best examples of their kind outside of Japan. For Shoji, Frances and their three children, Sono, Teru, and Tim, this would become a place where they could escape the mounting challenges that stemmed from their contrasting cultural backgrounds and interracial family.

Attack on Pearl Harbor

On October 5, 1937, President Franklin D. Roosevelt gave his famous "Quarantine Speech" in Chicago,

asserting that America must try to isolate itself from the growing contagion of war in Europe and Asia. But when Pearl Harbor was attacked on December 7, 1941, non-involvement in the war was no longer an option. America declared war on Japan.

Osato family perseveres

Despite their father's internment, the Osato family thrived during the war. Sono left home in 1934 at age 14 to join the famous Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo.

She turned into a national sensation, performing around the world and across the country—except in California, where it was illegal for her to enter during the war. Teru, their second daughter, married a U.S. naval officer and started a family in Norfolk, Virginia. Tim, the family's only son, joined the 442nd Regimental Combat Team of the United States Army to fight on the front lines in Europe.

Chapter 13

1945-52

Peace Treaty Ends War

Nagasaki and Hiroshima bombed

President Truman ordered the first atomic bomb to be dropped on the city of Nagasaki on August 6, 1945, and the second on Hiroshima

three days later, resulting in over 100,000 immediate deaths and leading to the unconditional surrender of Japan. Allied troops would occupy Japan for seven years.

Signing the peace treaty

In September 1951, a peace treaty came into force and officially ended the war nearly 100 years following the "opening" of Japan

by the United States, and 60 years following the arrival of the Phoenix Pavilion. With renewed hope, the two countries would start over on a path toward peace and prosperity.

During the surrender ceremony held on the deck of the Missouri, a special flag from Commodore Matthew Perry's ship that opened Japanese ports for trade was displayed. Accepting the surrender on behalf of the Allied Powers was General MacArthur, who was a cousin of Commodore Perry.

Cultural and economic boom

In the 1950s and 60s, the Japanese and U.S. economies expanded at unprecedented levels.

Advances in manufacturing and technology grew companies such as Toyota and Sony into leading corporations on the international market. By the late 60s, Japan's economy was the second strongest in the world. Its restoration after WWII was seen as complete with the success of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. These games in the minds of many signaled Japan's emergence from military defeat.

Chapter 14

1960-70

Yoko Ono

& the 1960s

A lifelong mission for peace

Through art, music and social activism from the 1960s to today, Yoko Ono remains a steadfast voice for peace and human rights.

Yoko Ono, whose name means "ocean child" in Japanese, transcends geography and time as a true global citizen whose work and life celebrate commonalities that make all of us one. In Jackson Park, SKYLANDING is Ono's first permanent public artwork in the Americas, and a marker of her place as an artist of profound international influence through her lifelong mission for world peace.

Chapter 15

1970–93

Growing Our Relationships

From garden to sanctuary

In its neglected condition, the island that was once graced by the Phoenix Pavilion became overgrown

and developed into a refuge for varieties of migrating birds, including herons, falcons, cardinals, catbirds, robins, yellow warblers, and geese. By the early 1970s, conservationists embraced the area as an extraordinary wildlife ecosystem, and the island was designated as the Paul H. Douglas Nature Sanctuary in 1977.

Osaka Japanese Garden

In 1993, in celebration of the 20th anniversary of Chicago's sister-city relationship with Osaka, the Japanese garden was renamed

the Osaka Japanese Garden. The City of Osaka donated funds for the construction of a new entrance gate. The year 2002 saw a complete renovation of the ponds and stone settings. Today, visitors to the Wooded Island can experience one of the most compelling connections to nature in an urban setting in the U.S.

Chapter 16

2005–11

Ranma Restoration

Finding a permanent home

Two panels were originally given to the University of Illinois at Chicago, and two to the Art Institute by the Chicago Park District.

Janice Katz, Associate Curator of Japanese Art at the Art Institute, first examined these panels in 2005, when they were on public display at UIC's Henry Hall. With both parties concerned about their condition, in 2008, it was decided that the Art Institute would be the best new permanent home for all four panels.

Restoration of the iconic artwork

All four panels were conserved and partially restored by the Litas Liparini Studio in Evanston.

The treatment involved structural stabilization, cleaning, pigment consolidation, toning, and re-carving of many elements such as birds' heads. The ranma panels, the focus of intense public and scholarly interest, are now on permanent display in gallery 108 at the Art Institute, together again for the first time since 1946.

Chapter 17

2011–FUTURE

The Future Rises

A new era is dawning

In Jackson Park, the future of Japanese-American relations is rising again from old roots.

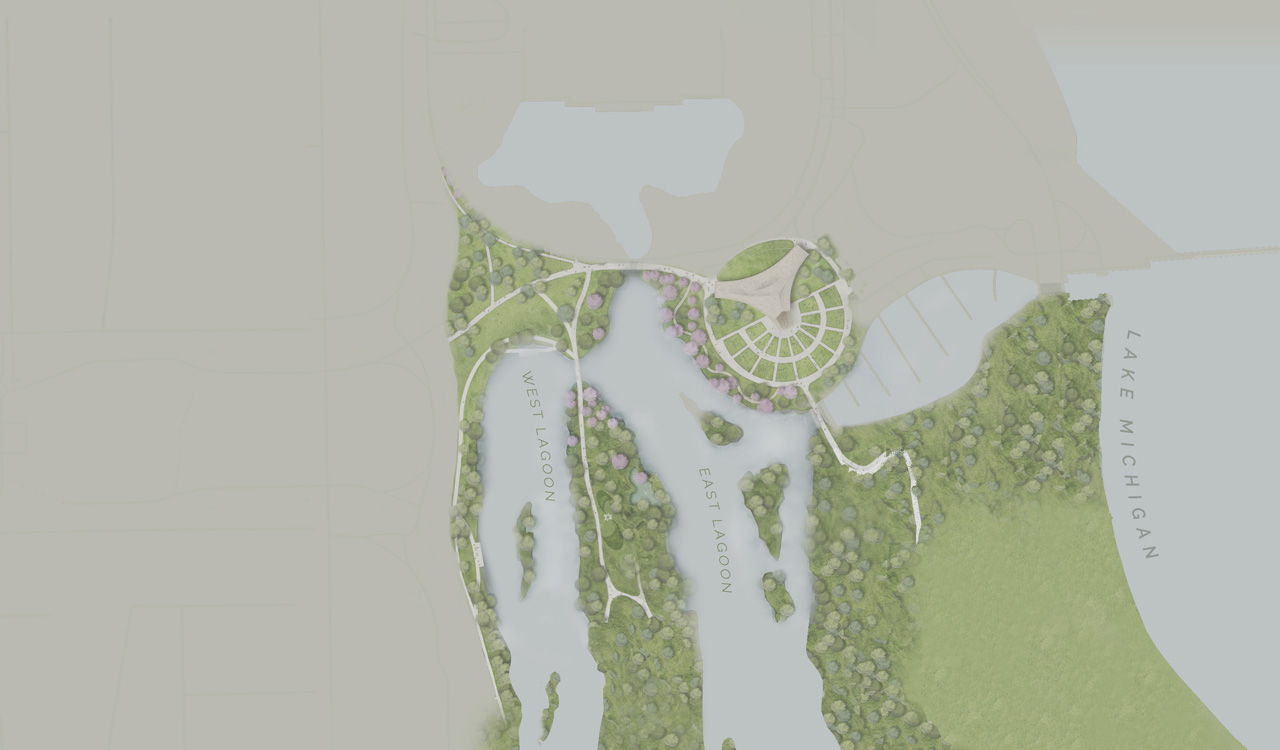

Starting with the 2013 planting of cherry blossom trees and the revitalization of the park, improvements respect, preserve, and renew the character of the landscape as designed by Olmsted after the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition, while addressing current and future issues and needs.

Space for enlightenment and discovery

"I want the sky to land here, to cool it, and make it well again."

–Yoko Ono

Upon her first visit to the island in 2013, Yoko Ono felt a powerful connection to the stories of the Phoenix Pavilion's creation and demise. SKYLANDING is the first large-scale public commission by Yoko Ono in the U.S., and will live on the pavilion's original location.

SKYLANDING brings Ono's personal sense of hopefulness to the public realm and gives visitors a communal connection to earth and sky as a place of contemplation and congregation.

The Phoenix Rises Again

Plans for a new pavilion are underway to make it a space where people and ideas will intersect and converge.

Designed by architect Kulapat Yantrassast, who was mentored by world-renowned architect Tadao Ando, the new pavilion will serve as a center of activity and learning for visitors.

The Garden of the Phoenix

Be a Part of the Future

The Garden of the Phoenix celebrates a rich history of friendship, peace, turmoil and growth between the two countries. And once again, the park offers a place in Chicago's South Side to gather, play, and relax just as it has in the past.

You can become part of the future of the park and its story.